Assessment Feedback Research – Affective, Behavioural, Cognitive Responses

What are secondary school teachers and students’ experiences of assessment feedback? What are students’ cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to feedback? This was what our research team sought to investigate in the study ‘Secondary School Teachers’ and Students’ Experiences of Assessment Feedback’. Preliminary findings were recently shared on 5 February with the five schools that participated in the research study. The sharing session also provided an opportunity for the research team to get the participants’ views on the findings. Here we present some findings and selected comments shared by our participants at the end of the session.

Students’ receptivity and emotional response to feedback

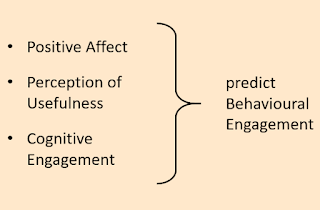

A survey was first conducted with fifteen classes of secondary three students. The survey consisted of a baseline survey and three cycles of post-feedback survey that were given to the students during their English class when their teachers gave them back their marked written essays. The survey comprised 3 sections. The first section asked students to rate their emotions on a 5-point Likert scale when they receive feedback from their teachers on their writing. The second section was the Receptivity to Instructional Feedback (RIF) scale which comprised 37 statements that students rated based on how much they agree with the statements, also on a 5-point Likert scale. Factorial analyses of the 37 items resulted in 4 factors – Positive Affect, Perceptions of Usefulness, Cognitive Engagement and Behavioural Engagement (see table 1 for a summary of the factors, their descriptions and examples of the survey item). The last section was a general appraisal, also rated on a 5-point agreement Likert scale.

| Positive Affect | Feelings of enjoyment when receiving teachers’ feedback e.g. I enjoy reading teacher’s comments on my tests/assignments.

|

| Perceptions of usefulness | Places value on receiving teacher’s feedback e.g. Teacher’s feedback is very effective in helping me enhance my performance.

|

| Cognitive Engagement | Understands the feedback e.g. I understand how to use the feedback that I get.

|

| Behavioural Engagement | Acts on the feedback e.g. When I receive feedback, I carefully read every comment.

|

Make sure that we involve the students emotionally as well. If they feel it, they will be better able to act upon it.

But what specifically about the feedback that students enjoy or find it easier to understand that encouraged them to act on it? Our team delved further into the data to look at patterns of feedback, analysing the written essays with feedback, as well as what the students said about them. It was found that general praises like “Good effort” did not make much of an impression on students as it did not give them much guidance on how to improve. Students were more encouraged when feedback specifically mentioned what they did well:

I would like to see a more detailed analysis, like for example if I’ve written a very, very good sentence or a good objection… [the teacher] can bracket my sentence and put a tick across… to encourage me, that what I’m doing is on the right track. The teacher can add on to the ‘keep it up’ by writing more feedback. …detailed feedback on what I can improve on. Like, ‘You can start the sentence by, I think you can dot dot dot,’ so that it is more targeted and so that I know what to focus on.

Another finding was students’ behaviour when their teachers expected them to act on the feedback, for example in terms of rewriting their entire work or parts of it. When students face an error they do not know how to correct, they may skip doing it. Figure 3 shows an example of a student editing some areas (in green ink) while appearing to ignore others (circled in blue below).

Because in the context if you think, “Oh, rewrite the whole essay or writing,” then it’ll be like, “Argh!” You know? Need to write some more paragraphs and all that. But if [the teacher] said, “Oh, write the one that you are interested in,” and then, you know, try to improve on that, I think it’s much better.

Some teachers involved in the study made deliberate attempts to ensure students reflect on their work prior to submission. This could be in the form of a success criteria checklist or a feedback cover sheet (where students wrote what they felt they did well and requested teachers to comment on specific areas of their writing. See Figure 4 for an example).

I actually remembered what she said to improve on my last point, my last paragraph and I actually wrote in a complete… in a better paragraph.

From the patterns of feedback discussed above, two themes emerge – those of will and skill. Students appear more willing to act on feedback when they received specific affirmation of the things they did or were given the choice on which aspect of their writing they want to work on. However, their will to do something about the feedback (besides just reading it) depended as well on how much they understood and knew what to do with the feedback they received. Specific instructions and examples on how to improve their work might ensure more efficacious outcomes when students act on the feedback.

Suggestions from students on the uptake of assessment feedback also show their desire to have deeper dialogue with their teachers. One student suggested that the “…teacher can approach us for a heartfelt talk about how we feel towards that class and how [the teacher] can improve so that we can create a bond between the subject so that we can like the subject more.” Another mentioned, “…feedback has a different importance to every student…start of the year, the students can tell the teacher how they would like to receive feedback…because different students have different learning methods…maybe if feedback can be tailored more to how each student responds to the feedback.”

Give more thought and be more intentional about getting students to level up in terms of their engagement towards feedback i.e. introspection and greater self-efficacy

What about teachers’ thoughts on assessment feedback? Analyses of the teacher interview transcripts suggested a nested hierarchy with five levels of teachers’ conceptions. The least sophisticated conception is feedback as inspection, where the teacher simply acknowledges that the student has fulfilled the task and highlights what was wrong in the student’s writing. The second conception is one of correction, where the teacher does not only point out the errors but expects students to do some form of correction to ensure they do not make the same errors again. The third teacher conception goes a step further in helping students understand and process feedback by providing opportunities for verbal dialogue so that students can clarify doubts regarding the written feedback. This is feedback as consultation. Feedback as conversation, the next conception, does not stop at students’ understanding of feedback, but also ensures students’ application of feedback for subsequent tasks as well, thereby increasing students’ confidence with each cycle of feedback. The most sophisticated and ambitious conception is when the teacher not only does all the things mentioned above but also prompts students’ internal dialogue and feedback through reflection. Students’ choice, agency and critical thinking are at the heart of the feedback here. Table 2 summarises the nested hierarchy of conceptions.

|

|

1.Feedback as Inspection |

2.Feedback as Correction |

3.Feedback as Consultation |

4.Feedback as Conversation |

5.Feedback as Introspection |

|

Structural aspect:The theme of feedback |

Emphasizes students’ mistakes. |

Emphasizes students’ compliance. |

Emphasizes students’ understanding of feedback. |

Emphasizes students’ use of feedback. |

Emphasizes students’ reflecting on learning. |

|

Referential aspect:The attributed meaning to feedback |

Acknowledge-ment of what was done right for task fulfillment and grammatical errors. |

Information about structure, expression, and language errors. |

Ways of helping students understand and process feedback. |

Instructional dialogue integral to teaching. |

Reflective practice that promotes self-directed learning. |

Looking at the table, we learn that we might be able to change our conditions for feedback practice. The nested table is great at suggesting how we can progress from one column to the next, certainly while keeping in mind the current standards of the student in question. At the school level, if we are sharing the nested table with the teachers, we need to emphasise that the table does not label the teachers based on how they deliver their feedback. It really depends on the context, the school and the student’s profile.

Feedback is a complex process, made more complex with how students may respond. To ensure greater uptake of feedback, teachers should consider students’ responses to feedback, particularly in the affective, behavioural and cognitive domains as they adapt their practices for different students and different contexts.