by Mr Jerome Chong (MCT903)

Abstract

This study examines the ramifications and implications of assessment practices carried out with academically low progress learners (LPL) in a Singapore mainstream primary school. A primary 5 (P5) foundation stream class of 18 students were taught by the same teacher in English and Mathematics for 2 academic years until they sat for their Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE) paper at the end of primary 6 (P6). This study focuses on Assessment for Learning (AfL) practices and feedback provided by the teacher, by peers of the students and through teacher supervised Technology Enabled Applications (TEA). It investigates some of the challenges faced, courses of action taken and some suggestions to improve upon the results obtained.

Introduction

There are not many studies on AfL conducted on LPL in the primary school context in Singapore. This study discusses challenges that was faced when implementing AfL practices, the resultant courses of action that were taken, some solutions that were formed and the results that were achieved with LPL in a mainstream primary school in Singapore. This paper studies actual classroom examples of the class’ journey with the same teacher who was their Form, Foundation Level English (FEL) and Foundation Level Math (FMA) teacher for 2 years from P5 to P6 in the class of (initially) 18 LPL students who were banded in the Foundation stream at the beginning of P5 to “help them build strong fundamentals, and to give them the confidence to pursue learning at a pace and level that is more suited to them” (MOE, 2019). These students were placed in the foundation class as they had not been able to catch up with the syllabus from P1 to P4. Most had consistently fallen in the bottom 10% of the cohort in terms of overall academic results in the years prior to P5. However, the students in this study had improved their results with FEL passes increasing from 56% of the class passing at the P5 entry point, to 95% passing at the P6 year-end exams prior to the PSLE and FMA passes increasing from 6% at the beginning of P5, to 95% at P6.

Statistics by the Research and Management Information Division (2018) indicate that there are an average of 39,000 students in each cohort, of these about 4,000 (10% of cohort) offer FEL and/ or FMA at PSLE. The primary school in this study has students offering FEL and FMA figures similar to national statistics with 13% of its cohort offering these. LPL students are defined as “the 15–20% lowest academic scorers” in standardised examinations in the Singapore context (Wang, Teng & Tan, 2014).

Based on an ethnographic study of students in the Normal-Technical (NT) stream in a Singapore secondary school, the (NT) students had traits of ‘average’ self-esteem and academic achievement and poor study habits that worsened as they went on to Secondary 2. They possessed poor command of English and attention span and preferred less ‘critical’ and more ‘flexible’ teachers; their low literacy levels also compounded classroom management problems (Ismail & Tan, 2005). Another study found that students in the NT stream in secondary school are assumed to have poor behaviour, possess poor study habits and have low motivation and self-esteem. (Talib & de Roock, 2018). Similarly, in the primary school context, it was observed that LPL are from “low-income families who rarely use English as the medium of communication” (Wang et al, 2017). Most of the LPL’s academic success “intersect with other factors including poverty, racial or linguistic minority and learners are also identified as having special education needs (SEN)” (Kang & Martin, 2018). Students with SEN have “starting points often lower than those of other pupils” (Colum & McIntyre, 2019). Based on the past records of the primary school being studied, most of its LPL and foundation students end up in the NT stream in secondary school. The LPL in this class fit into the above descriptions with various family, personal or societal related issues. These are analysed at the class level and tabulated below:

It was surmised that LPL students have low achievement traits due to the levels of (1) Individual, (2) School/ education system and (3) Family and society. It was suggested that strategies to mitigate low achievement traits should target these three levels (Wang, Teng & Tan, 2014). Some strategies include “promoting mastery goal and growth-mindset and (by) providing effective feedback” (Talib & de Roock, 2018). The teacher in this study attributes much of the improvement in the students’ overall improved results to feedback and AfL practices that were implemented; Tan succinctly surmises that literature on formative assessment (FA) has three recurring emphases, one of them being “giving feedback that enables them (students) to improve their work” (Tan, 2013). AfL was defined as the “part of everyday practice by students, teachers and peers that seeks, reflects upon and responds to information from dialogue, demonstration and observation in ways that enhance ongoing learning” (Klenowski, 2009). This paper continues by demonstrating how effective feedback and AfL practices based on the two definitions above was used in this classroom had posed some challenges, how these were addressed and some solutions that were adopted. All names of students have been changed.

Teacher-led Feedback… of AfL, feedback, power and the curriculum,

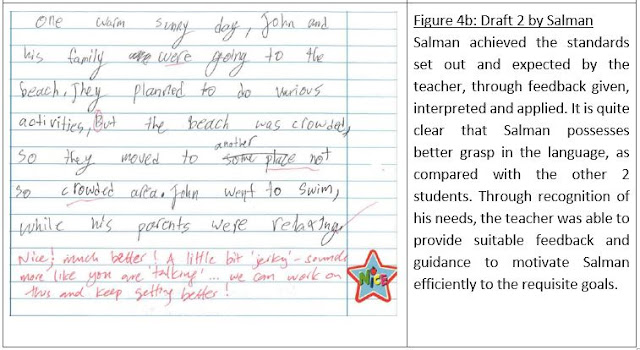

Tan (2013) presented a simplified model for AfL, where assessment standards was represented by the vertical axis, task design by the horizontal axis, and feedback practices by the incline, forming a “triangle of practices.” (Tan, 2013). In this class, the teacher had a clear understanding of each student’s background based on the three levels to mitigate low achievement (Wang, Teng & Tan, 2014). The teacher firstly set an assessment standard to be achieved by each student, before designing and timing the feedback to be given. This then had to be interpreted and applied by the learner and to be re-given as necessary.

About half of the class had failed English at entry point at P5 and by the end of 2019, all but the student with GDD had passed. The three students presented here are Terry, diagnosed with dyslexia, communicates in English at home with mum and siblings and in Mandarin with father and grandparents. Harshita, is a conscientious student who communicates mainly in Tamil with parents at home. Salman, diagnosed with ADHD, has several internal disciplinary cases and communicates well in English. Below is a sample of the students’ work on a continuous writing (CW) assignment where they were required to write the introduction of the CW based on the first picture of a CW assignment for the FEL stream.

It was also important to note that in the practice of feedback and dialogue with the student, the teacher had also built strong teacher student relationship (TSR). This is a “significant predictor of students’ academic engagement”. High quality TSR correlates with “self-esteem, level of competency and emotional connection”. (Talib & de Roock, 2018).

- Alderton, J. & Gifford, S. (2018). Teaching mathematics to lower attainers: dilemmas and discourses. Research in mathematics education, 2018. Vol. 20, No. 1, 53-69.

- Cheng, Y.S., Leong, W.S., and Tan, K. H. K. (2015). Assessment Rubrics for Learning. Assessment and Learning in Schools. Singapore: Pearson Education South Asia Pte Ltd.

- Chong, W. H., Huan, V. S., Quek, C. L., Yeo, L. S., & Ang, R. P. (2010). Teacher-student relationship: The influence of teacher interpersonal behaviours and perceived beliefs about teachers on the school adjustment of low achieving students in Asian middle schools. School Psychology International, 31(3), 312–328.

- Cizek, G.J. (2009). An introduction to formative assessment- History, characteristics and challenges. Handbook of formative assessment. Great Britain: Routledge Ltd, 3-17.

- Colum, M. & McIntyre, K. (2019). Exploring Social Inclusion as a Factor for the Academic Achievement of Students Presenting with Special Educational Needs (SEN) in Schools: A Literature Review. REACH Journal of Special Needs Education in Ireland, Vol. 32.1 (2019), 21–32.

- Crawford, L. (1995). Cooperative Learning in Singapore Primary Schools: Time for Reflection. Teaching and Learning, 16(1), 12-16.

- Dickson, J. (2011) Humiltas. Michigan: Zondervan.

- Dunne, M., Humphreys, S., Dyson, A., Sebba, Gallannaugh, F. & Muijs, D. (2011). The teaching and learning of pupils in low-attainment sets. The Curriculum Journal, Vol. 22, No. 4, December 2011, 485–513.

- Ee, L.L. & Joseph, J. (2011). Paving the Fourth Way: The Singapore Story. Singapore, National Institute of Education.

- Francis, B., Hodgen, J., Craig, N., Taylor, B., Archer, L., Mazenod, A., Tereshchenko, A. & Connolly, P. (2018). Teacher ‘quality’ and attainment grouping: The role of within-school teacher deployment in social and educational inequality. Teaching and Teacher Education 77 (2019), 183 -192.

- Gopinathan, S. (2012). Fourth Way in action? The evolution of Singapore’s education system. Educational Research for Policy and Practice. New York: Kluwe (Issue 11:1, pp. 65-70).

- Hargreaves, A., & Shirley, D. (2009). The fourth way: The inspiring future for educational change. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Hattie, J. & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112.

- Ismail, M. & Tan, A.L. (2005). Voices from the Normal Technical World- An ethnographic study of low-track students in Singapore. Singapore, National Institute of Education, Centre for Research in Pedagogy and Practice.

- Kane, M. T. (2001). Current concerns in validity theory. Journal of Educational Measurement, 38(4), 319-342.

- Kang, D.Y. & Martin, S.N. (2018) Improving learning opportunities for special education needs (SEN) students by engaging pre-service science teachers in an informal experiential learning course, Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 38:3, 319-347.

- Klenowski, V. (2009). Assessment for Learning revisited: an Asia-Pacific perspective. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 16: 3, 263 – 268.

- Klenowski, V. (2015). “Fair Assessment as Social Practice.” Assessment Matters 8: 76 – 93.

- MOE, Singapore (2017). PRESS RELEASES- Nurturing Future-Ready Learners – Empowering Students in Self-Directed Learning. Retrieved from https://www.moe.gov.sg/news/press-releases/nurturing-future-ready-learners—empowering-students-in-self-directed-learning .

- MOE, Singapore (2018). PRESS RELEASES- ‘Learn For Life’ – Preparing Our Students To Excel Beyond Exam Results. Retrieved from https://www.moe.gov.sg/news/press-releases/-learn-for-life—preparing-our-students-to-excel-beyond-exam-results .

- MOE, Singapore. (2019a). Learn For Life – Remaking Pathways- Greater Flexibility With Full Subject-Based Banding. Retrieved March 20, 2019, from https://www.moe.gov.sg/news/press-releases/learn-for-life–remaking-pathways–greater-flexibility-with-full-subject-based-banding .

- MOE, Singapore. (2019b). Updates to PSLE 2021 Scoring System – Enabling Students to Progress, Regardless of Starting Points. Retrieved on 10 Nov 2019 from https://www.moe.gov.sg/news/press-releases/updates-to-psle-2021-scoring-system–enabling-students-to-progress–regardless-of-starting-points .

- Munshi, C. and C. Deneen (2018). Self-regulated Learning and the role of Feedback. Cambridge Handbook of Instructional Feedback. A. A. Lipnevich and J. K. Smith.

- Oakes, J. (1985). Keeping track: how schools structure inequality. London: Yale University Press.

- Ong, Y.K. (2018). Helping Singapore’s students to learn for life. Retrieved from https://www.todayonline.com/commentary/helping-singaporean-students-learn-life .

- Parkin, H., Hepplestone, S., Holden, G., Irwin, B., & Thorpe, L. (2011). A role for technology in enhancing students’ engagement with feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, Electronic First Edition.

- Ratnam-Lim, C.T.L. & Tan, K.H.K. (2015). Large-scale implementation of formative assessment practices in an examination-oriented culture. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice. Vol. 22, No. 1, 61–78, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2014.1001319.

- Research and Management Information Division (2018). Education Statistics Digest. Singapore, Management Information Branch, Ministry of Education.

- Sadler, D. R. (2007). Perils in the meticulous specification of goals and assessment criteria. Assessment in Education, 14(3), 387 – 392.

- Sahlberg, P. (2011). Finnish lessons: what can the world learn from educational change in Finland? New York: Teachers College.

- Stodberg, U. (2011). A research review of e-assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, Electronic First Edition.

- Talib, N. & de Roock, R. (2018). Motivation Strategies for Academically Low-Progress Learners. NIE Working Paper Series No. 12, Singapore, Office of Education Research, NIE/NTU.

- Tan, K. (2013). A Framework for Assessment for Learning: Implications for Feedback Practices within and beyond the Gap. ISRN Education, Vol 2013, Article ID 640609.

- Tan, K.H.K. (2016). Asking questions of (what) assessment (should do) for learning: the case of bite-sized assessment for learning in Singapore. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 16(2), 189-202.

- Tan, K. H. K. and H. M. Wong (2018). Assessment Feedback in Primary Schools in Singapore and Beyond. . The Cambridge Handbook of Instructional Feedback. UK, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tay, H. Y. (2016). Longitudinal study on impact of iPad use on teaching and learning. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1-22.

- Tay, H, Y. (2017). A prototype twenty-first century class: a school-wide initiative to engage the digital native. In S. Choo, D. Sawch, A. Villanueva, R. Vinz (Eds.), Educating for the 21st Century. Springer.

- The Straits Times (2018). Changes to school assessment: What you need to know. Retrieved from https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/education/changes-to-school-assessment-what-you-need-to-know.

- Timmis, S., Broadfoot, P., Sutherland, R., & Oldfield, A. (2015). Rethinking assessment in a digital age: opportunities, challenges and risks. British Educational Research Journal, 42.

- Wang, L.Y., Teng, S.S. & Tan, C.S. (2014). Levelling Up Academically Low Progress Students in Singapore. NIE Working Paper Series No. 3, Singapore, Office of Education Research, NIE/NTU.

- Wang, L., Tan, L., Li, J., Tan, I. & Lim, X. (2017). A qualitative inquiry on sources of teacher efficacy in teaching low-achieving students. The Journal of Educational Research 2017, Vol. 110, No. 2, 140 – 150.

- Watson, A. (2002). Instances of mathematical thinking among low attaining students in an ordinary secondary classroom. Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 20 (2002) 461–475 .

- Teo, Y. Y. (2018a). This is what inequality looks like. Singapore: Ethos Books.

- Teo, Y. Y. (2018b). When kids say “I lazy what”. The Straits Times. Retrieved from https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/when-kids-say-i-lazy-what.